It’s difficult to actually create something new.

Our ability to describe what happens in the process is getting better, as more is known about innovation, creative processes, solving "wicked problems," and the notion of design thinking. It relates to a willingness to get lost in a problem, and possibly the use of abductive reasoning. However, the understanding where a new idea forms and sticks remains elusive and complex as the human brain itself.

We think about and experience creative processes every day, and have developed a visual model for thinking about the process which helps us better understand the process and describe it to others.

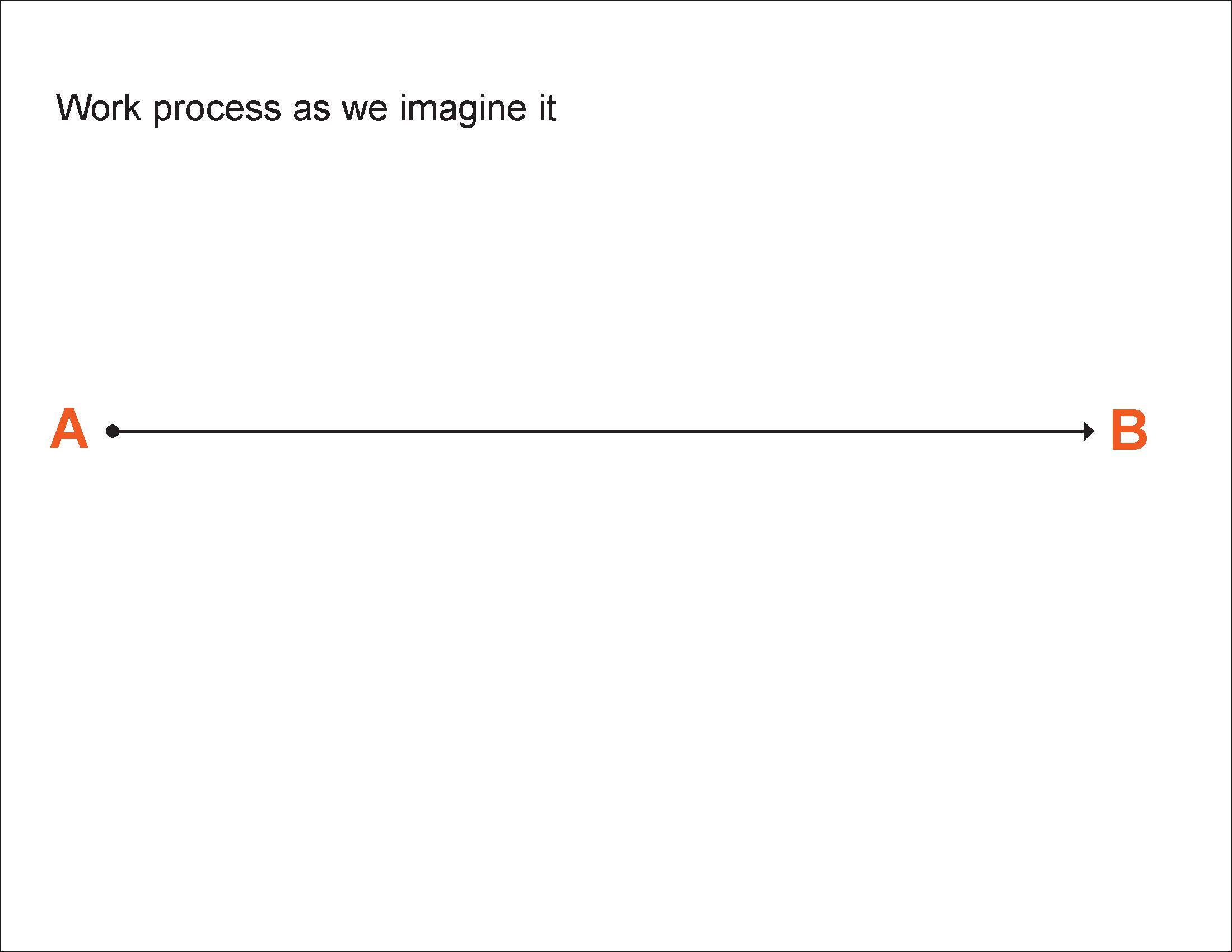

First, you might start with how many would like to see problems and solutions: A straight line – the shortest distance from point A (problem) to point B (solution).

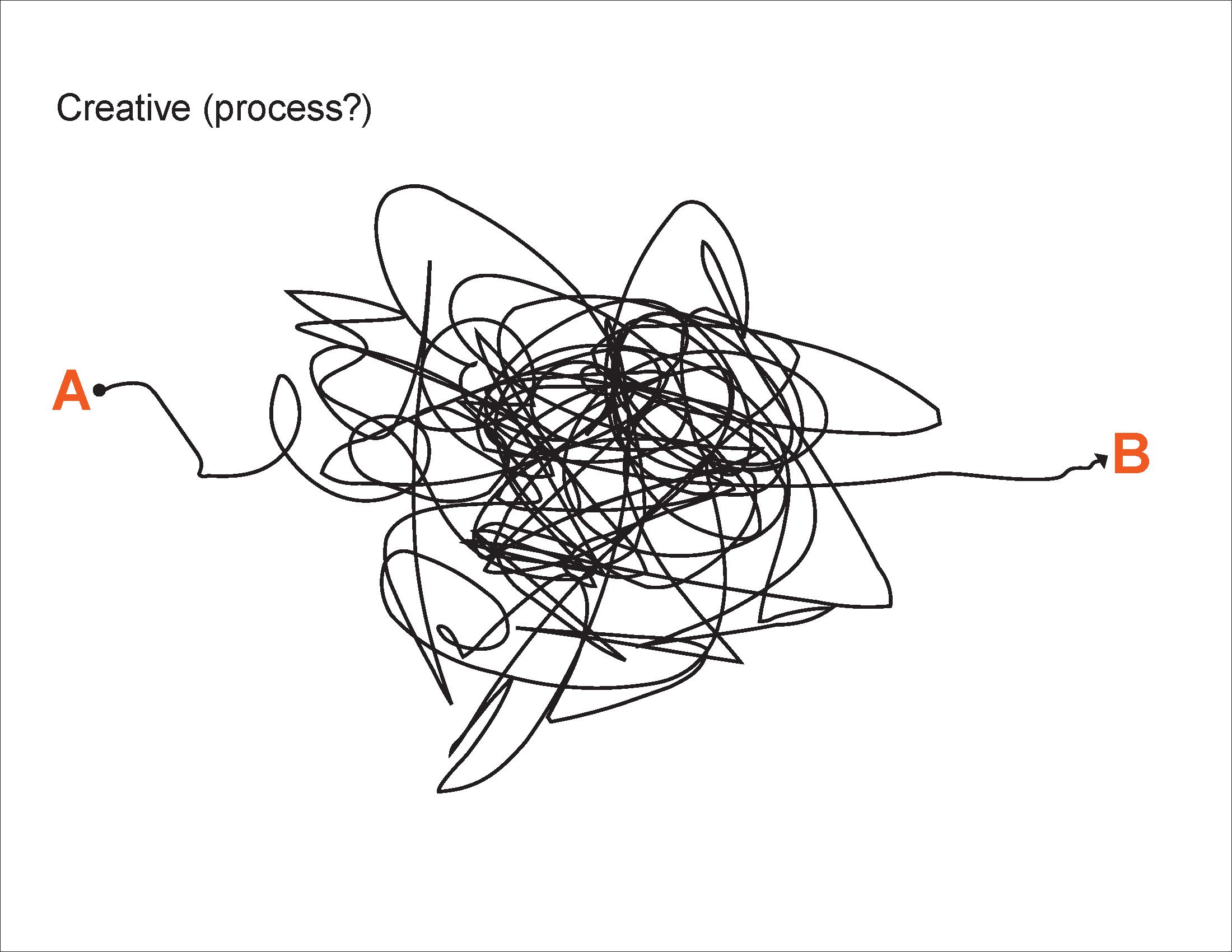

When you are busy optimizing known processes, it’s easy to think that perhaps all process look like this. They don’t. If predictable processes are a single uncooked spaghetti noodle, an average actual creative process is more like a box of cooked spaghetti flung onto a wall. It might look more like the human brain itself.

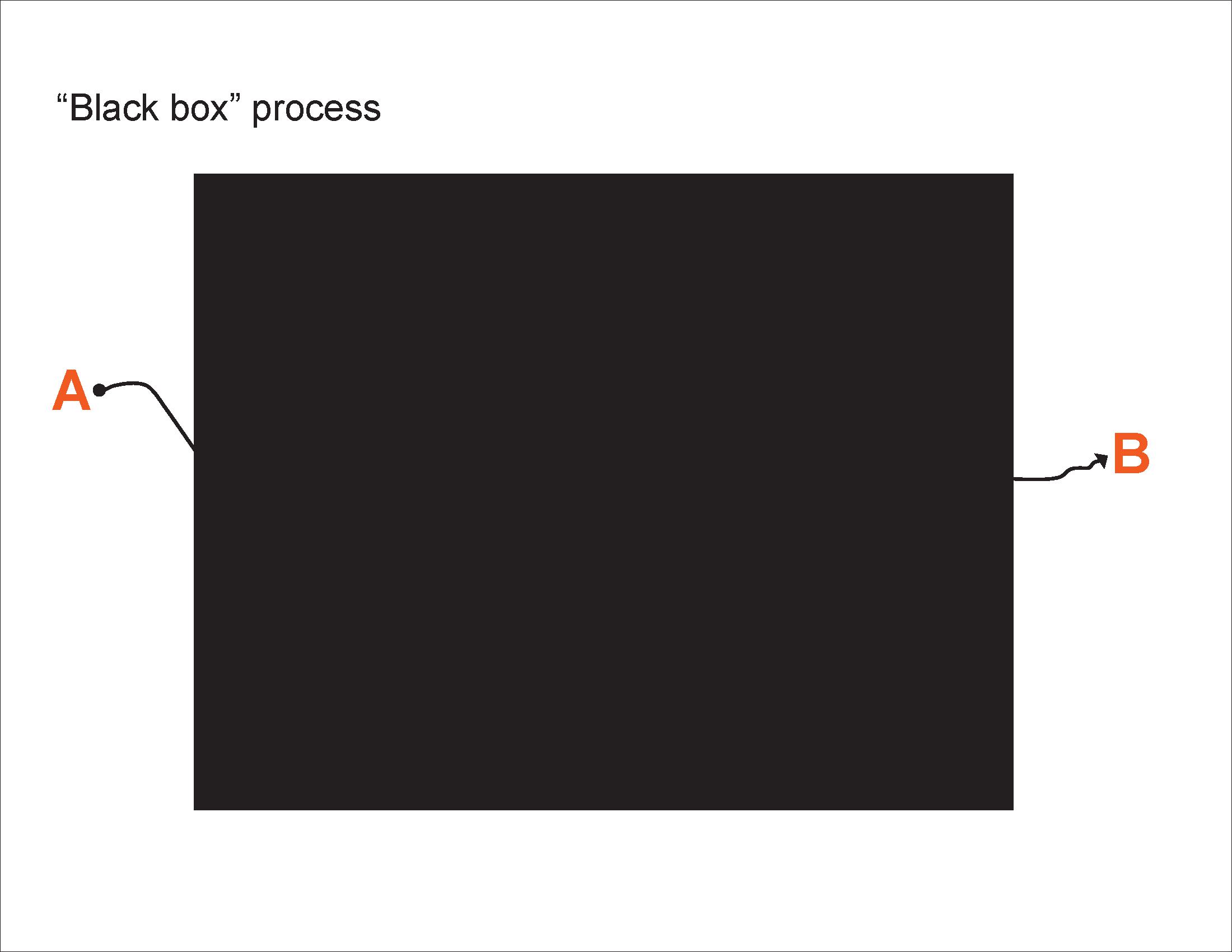

Some “creative” people talk more about creative processes than follow them. To others, the creative processes are a mystery – a black box. While the actual process is cooked spaghetti, it’s hidden behind a veil. It may feel like it’s a straight line even when it’s not.

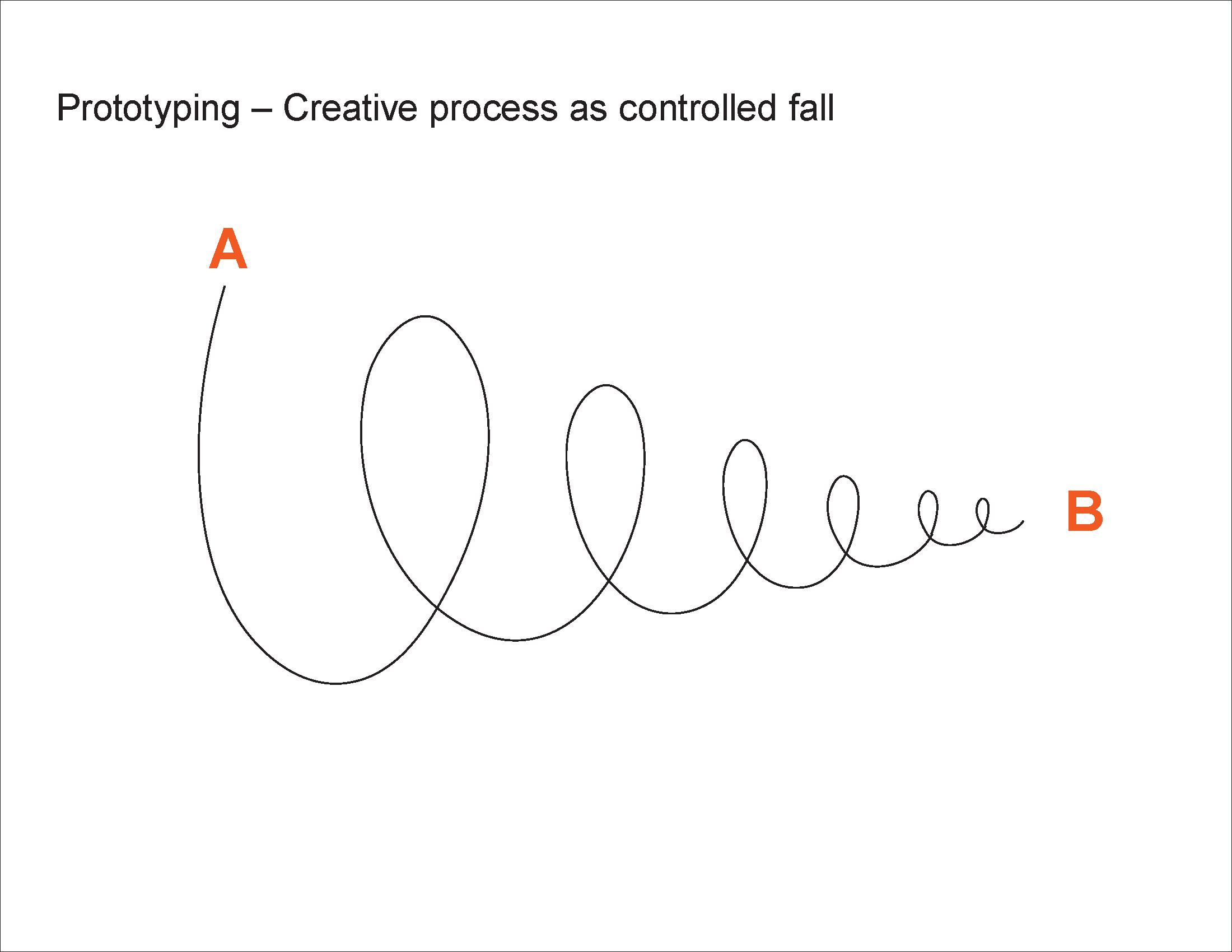

These processes can be controlled to a degree. Think about it as a controlled fall. You need to explore options, but a gravitational pull should govern the general direction. Prototyping is a key part of any creative process – building to learn. Creators generate ideas based on an informed hypothesis, then they test and course correct. This leads to a kind of deliberate meandering, which is what progress looks like.

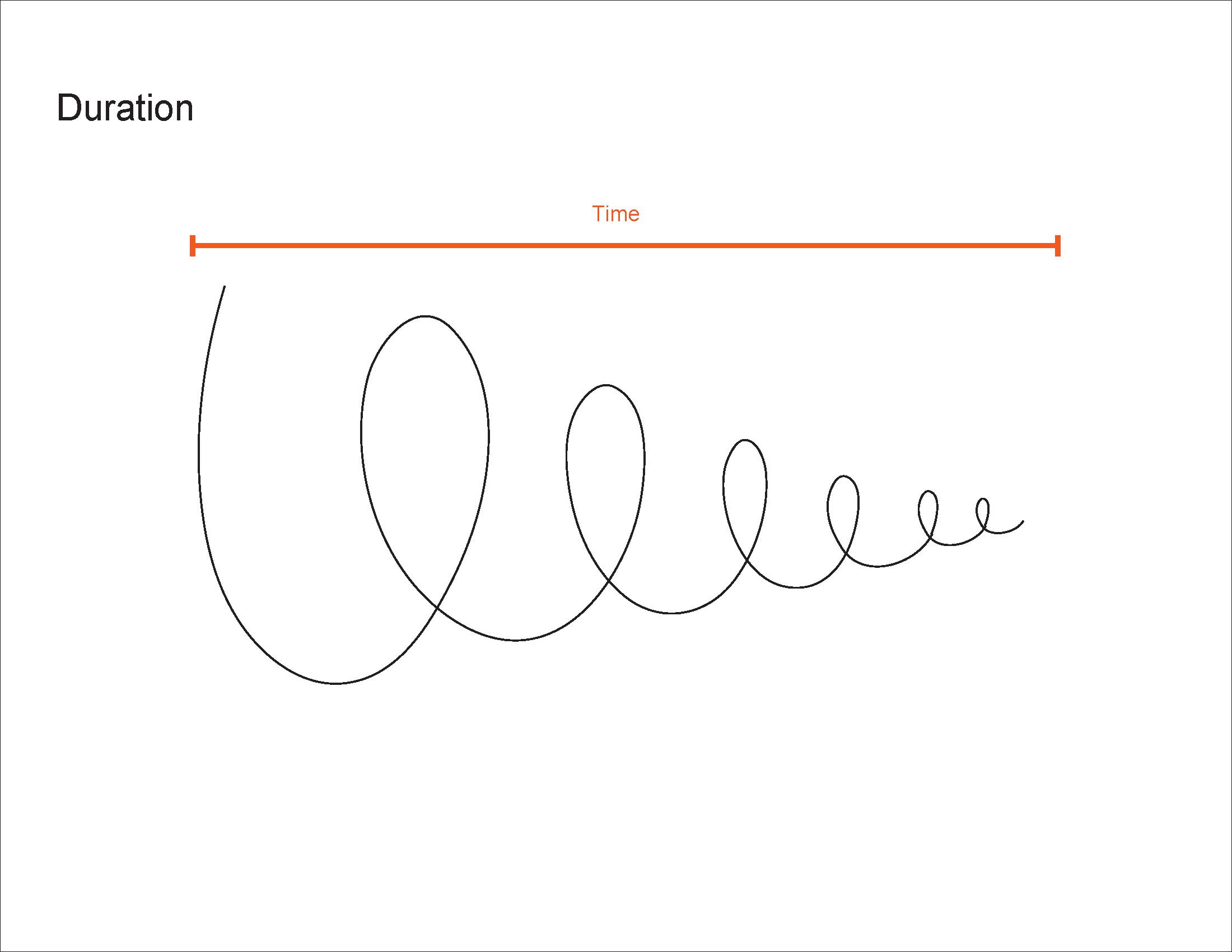

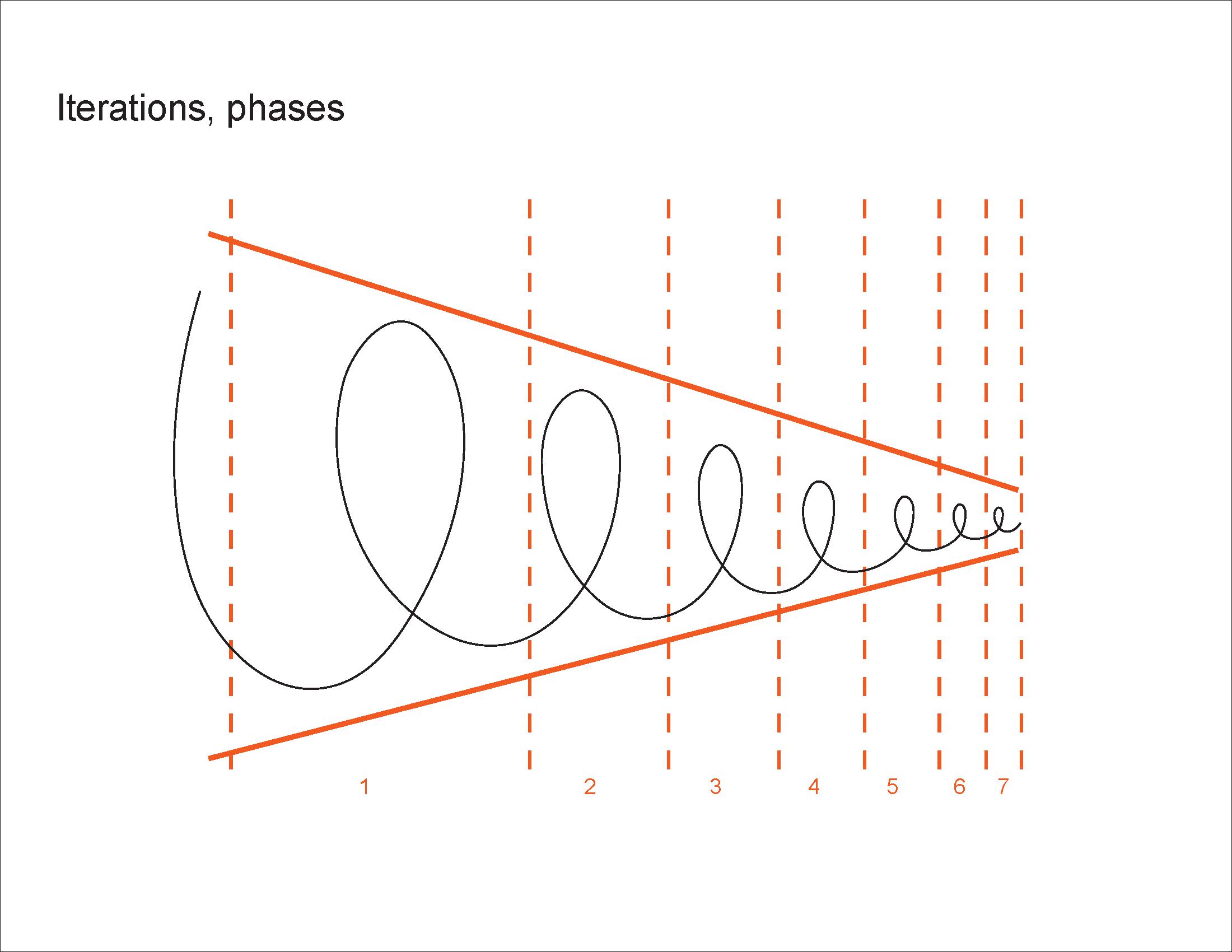

You can visualize this controlled fall, this iterative process, as a spiral. View the length of the spiral as a measure of time. The more time you have, the wider the spiral.

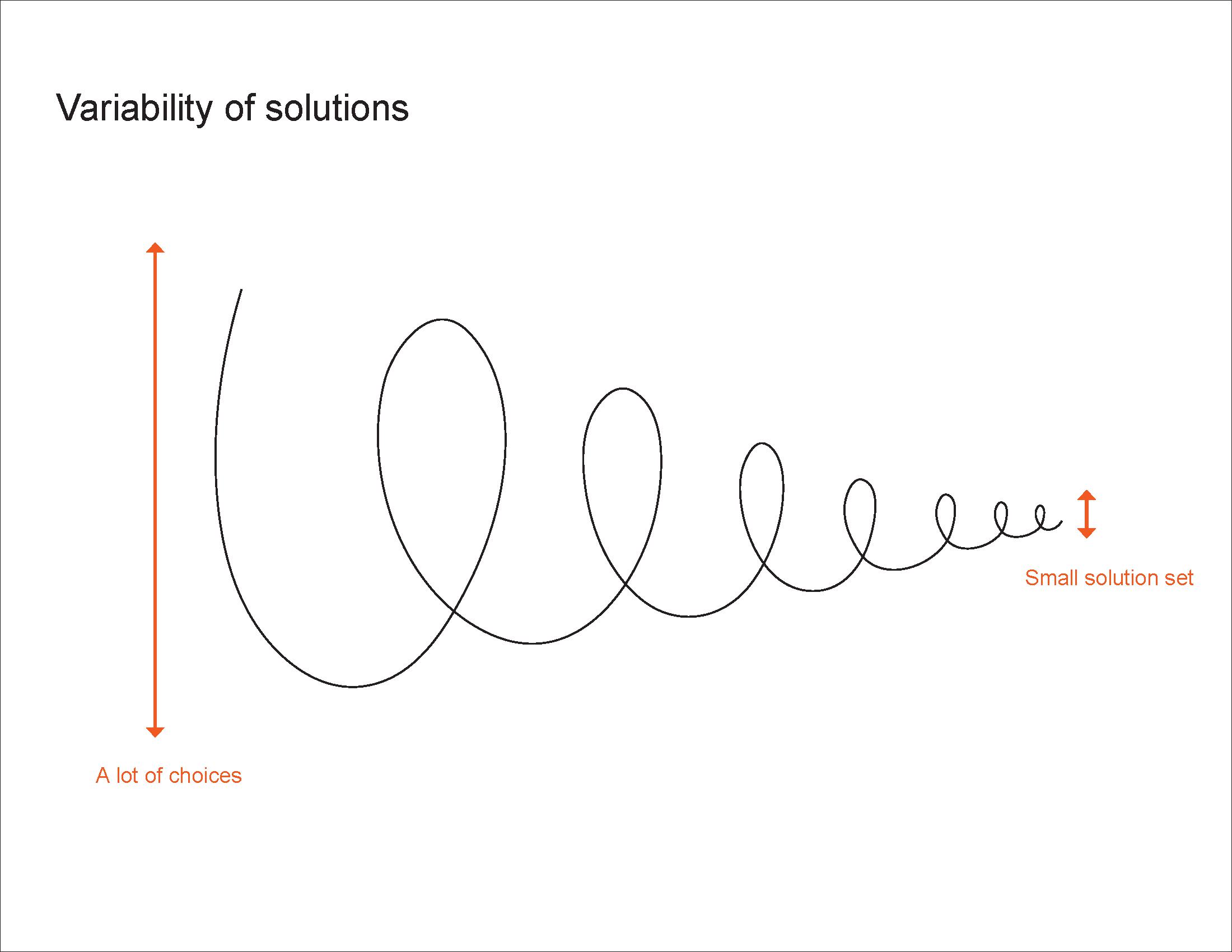

If the horizontal axis is duration, the vertical axis can be the number or variability of possible solutions. A taller spiral suggests more varied possible solutions. Tighter spiral loops suggest a smaller solution set.

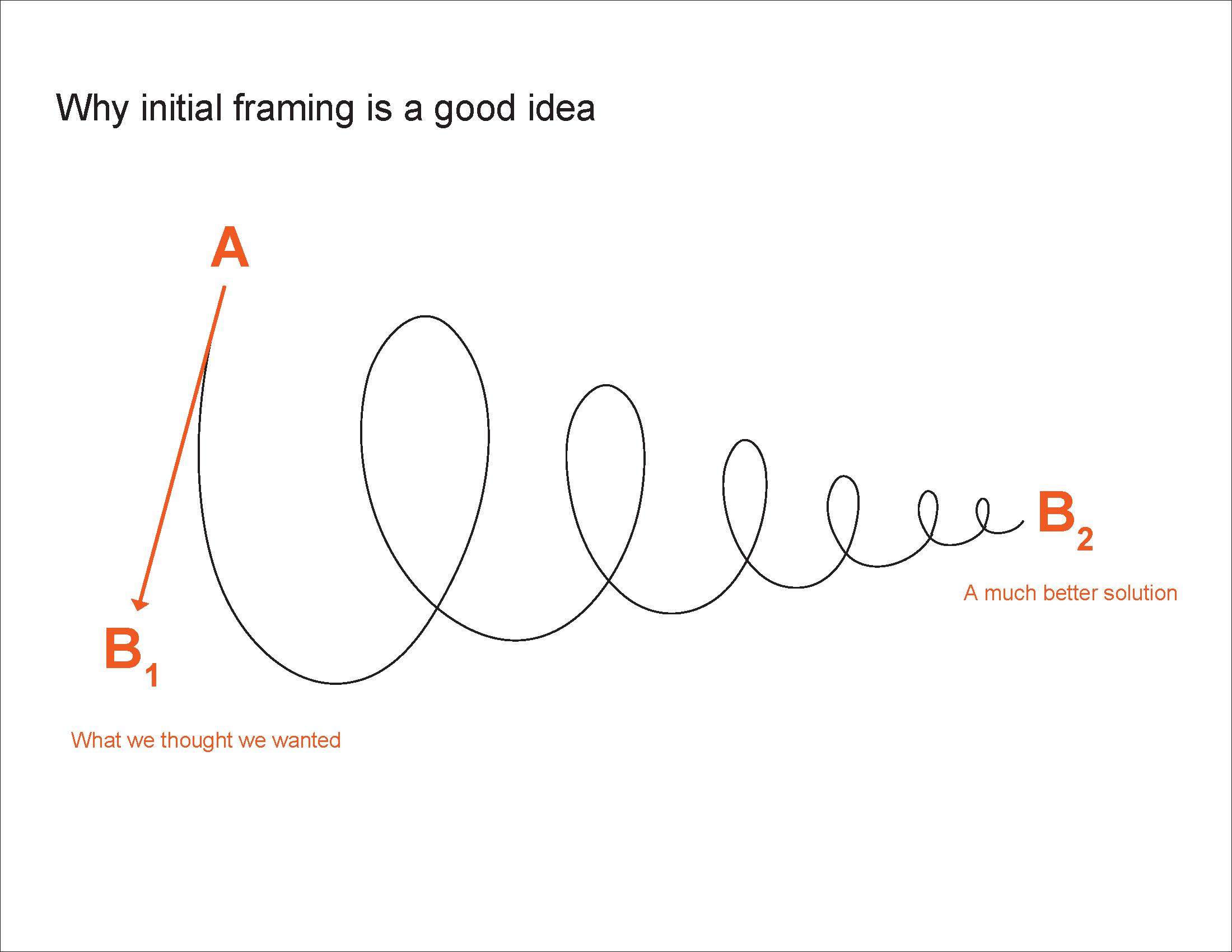

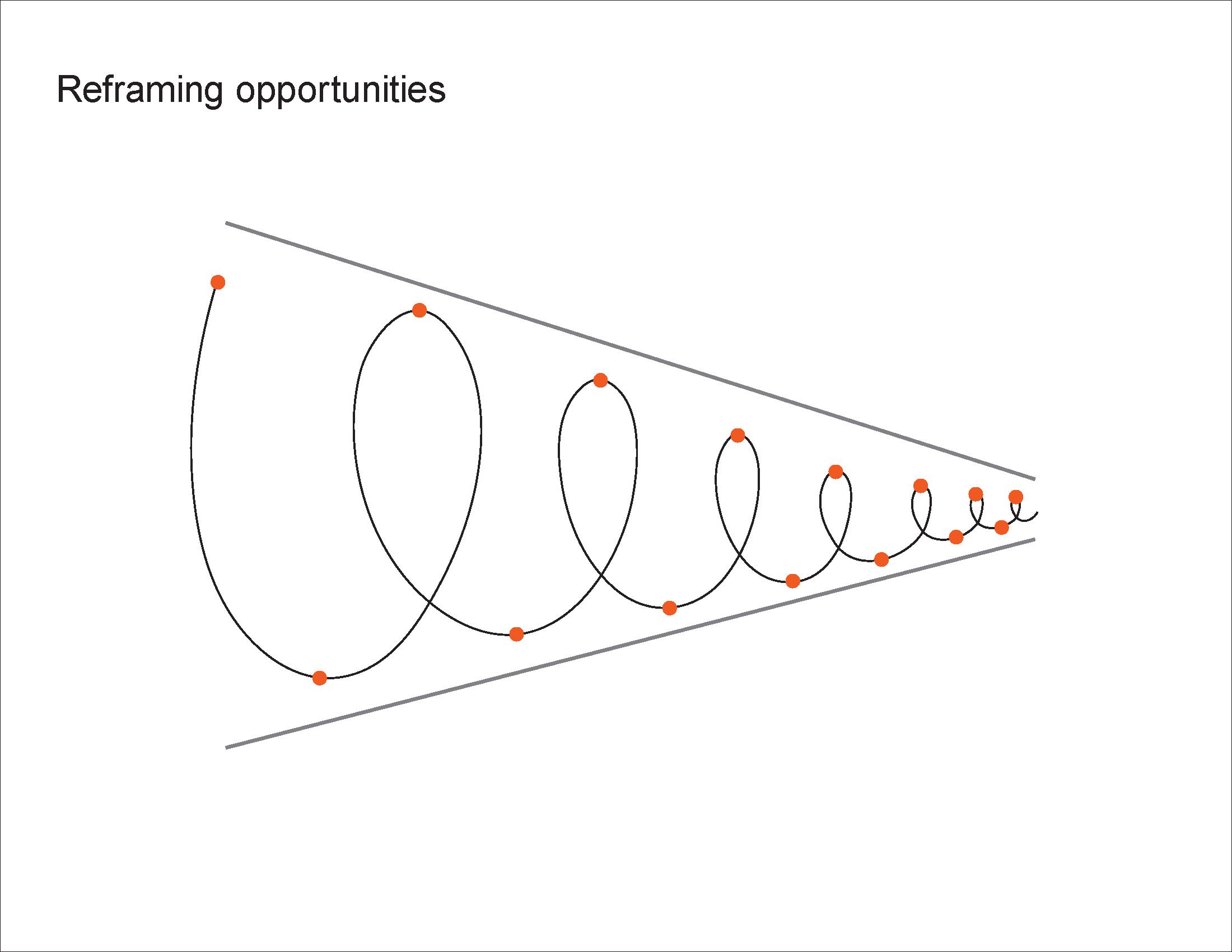

Framing and re-framing a problem is inherent is good problem solving. One way to think about this is that if we always solve the problem the way we initially view it, rather than adapting to what we learn by prototyping, we end up in a very different place (B2) than what we originally assumed (B1). What we thought we wanted usually doesn’t result in something new. If we knew exactly what it was before we started, it probably wouldn’t really be new

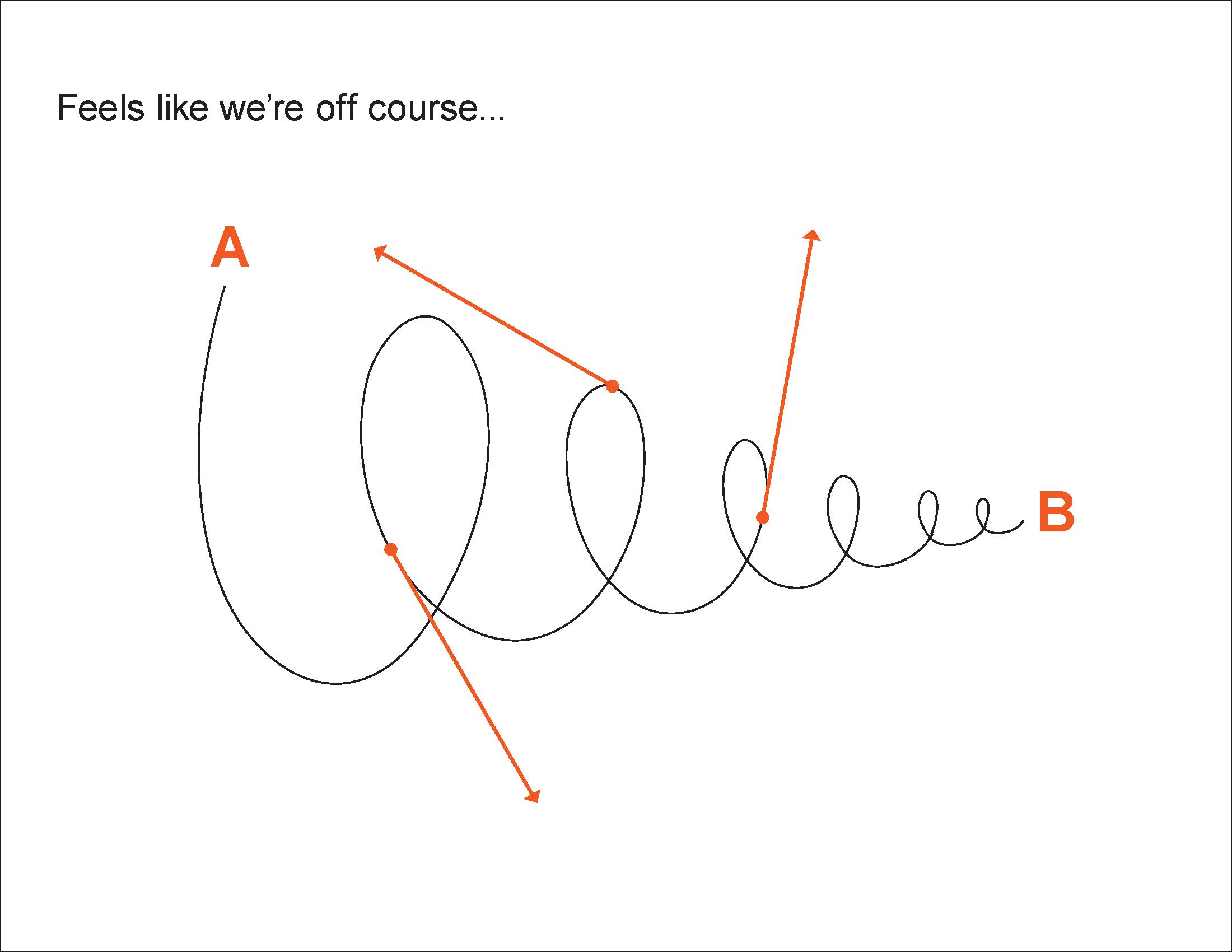

This kind of iterative, creative process can make some people uncomfortable. At times, it may actually feel like loosing traction. While it can feel like you’re off course, you often have to take a step back to take three steps forward.

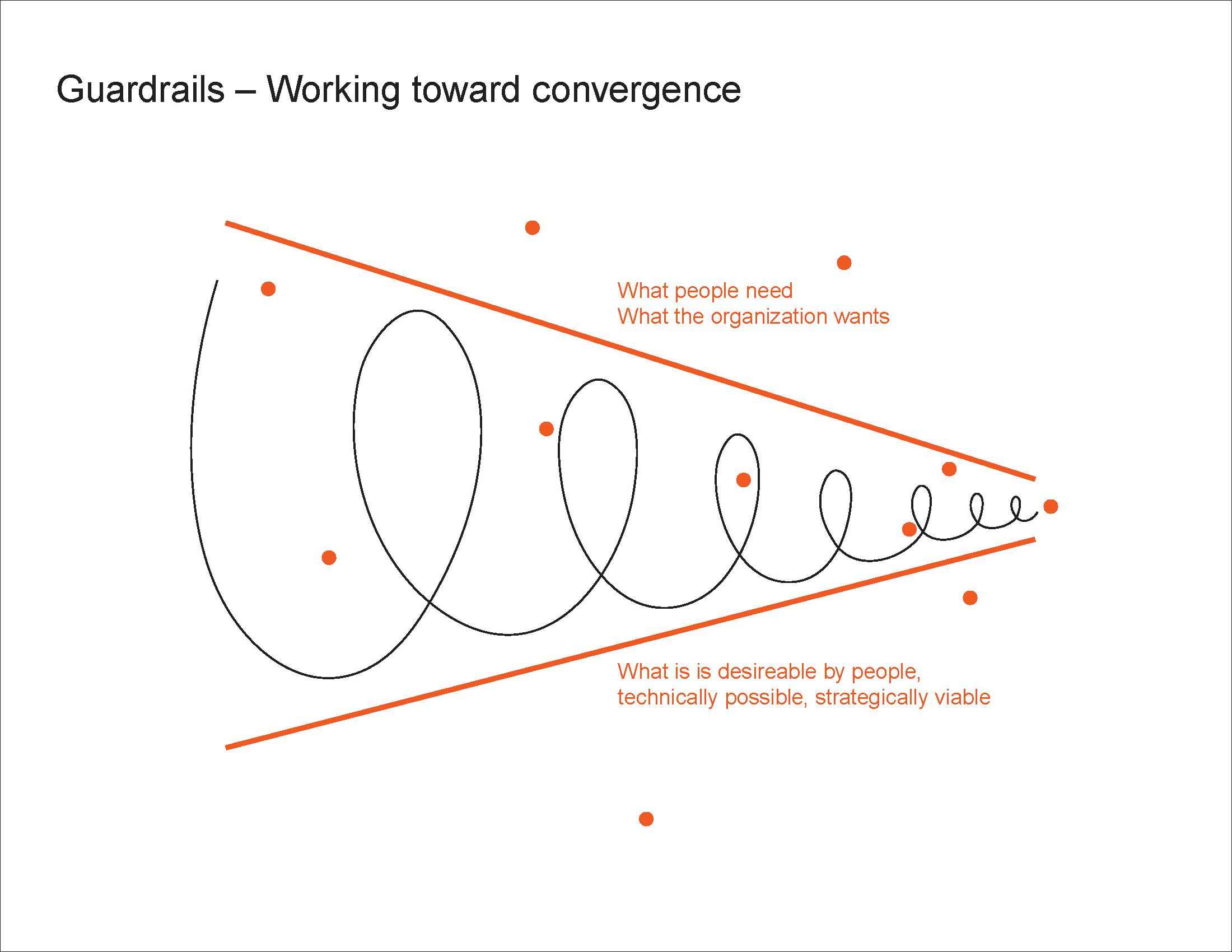

You can save yourself from complete chaos by being clear about your acceptance criteria. These creative parameters define a kind of funnel, which helps you track progress. These criteria should not be overly prescriptive, or have the solution baked into them. A properly framed problem helps determine which ideas push the effort forward, and which should be left on the cutting room floor.

Each turning point of an iterative creative process is an opportunity to re-frame the problem in tighter terms. We know much more by the third iteration than we did in the first. Be willing to re-frame the problem, informed by learning, to find your way to a better result.

Each loop in the spiral suggests an iteration. Being cognizant of how many iterations you want, can tolerate, or can afford, is a useful lens for managing a creative process. More iterations often yields better results, but there is a point of diminishing return.

Creative processes are predictably unpredictable. A visualization like this can help add structure to an otherwise unwieldy process. It won’t solve every problem, but spirals may be a better framework than waterfalls for creative processes.

Creating something new may never be as simple as going from point A to point B, but recognizing certain levers such as problem framing, re-framing, duration, variability of acceptable solutions, and the number of iterations, are creative problem solving principles which can enrich your vocabulary and understanding and managing what really happens.

As you better understand what goes on in the black box, you’ll have a better shot at actually creating something new.