Change can be hard to see. We see ourselves as well into a knowledge era, but its full effects may not yet be upon us. Changes underway can be hard to perceive or understand. It is even more difficult for organizations to adapt to these changes when they are guided by a philosophy of a previous era. New lenses are needed to chart the course for a new era.

Like the industrial revolution before it, the knowledge revolution will change our lives in profound and unexpected ways over the next century. Much of the information technology revolution has merely allowed us to do old things in new ways. More change is on the way. It’s helpful to know where we’ve been and where we might be going.

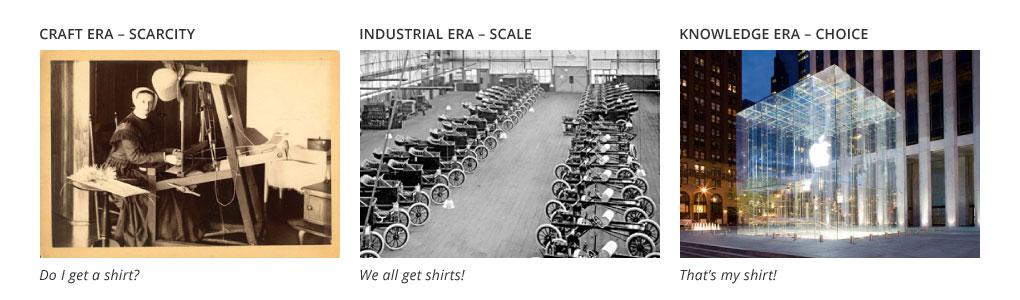

The industrial revolution led society out on era of scarcity to an era of abundance. Companies were built for scale, employing the technologies and strategies of the day to create enough supply to meet a rapidly growing demand. The previous revolution took place over many years largely because of slow communications, but we don’t have that problem today. Aside from challenges arising from emerging economies of scarcity conflicting with economies of abundance, which slow progress, we are rapidly coming to the close of the industrial age.

Evidence of Change

Signs of changes are all around us, as technology and globalization carve a new landscape. Web era darlings like Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Twitter are easy examples of companies writing a new playbook. Meanwhile, brand leaders like Nike, Apple, Starbucks, and Disney are doing something similar – experimenting with new models for creating and delivering value. It starts with selling books or music online, but it ends up transforming publishing and music. The promise of ubiquitous mobile computing and internet-enabled objects, not to mention self-driving cars and mapping the human genome, offer new opportunities for how we live.

While some firms are succeeding, others are languishing. Like a frog in tepid water, these seismic changes can be slow motion system shock to a business. Many companies are experiencing symptoms of stress. They experience stiffer competition, higher customer expectations, and changing market dynamics. Strategic planning has moved from 10 year horizons, to 3 years, to today when many question if strategic planning can actually help. A default mode is to redouble efforts – pedal harder. This may work for a while, but it’s not a sustainable advantage.

Companies that weather changes will understand and leverage new patterns of success. Strategic models are useful lenses to enhance understanding, but too often models get confused with reality. The map is not the territory. Strategic planning may be in question because the strategic models are out of date, or need to be adapted for today’s conditions.

New Paradigms

A common denominator is that these firms are not bound by their category. Industry language and measurement often defines – and results in limiting – a company’s perceived ability to change. While not every industry has the fluidity of the tech sector, category boundaries are often self imposed. Indeed, how to reframe one’s category or industry to better contextualize and optimize for today’s customer is a key objective for company leaders today.

When Nike acquired Cole Haan, it thought of itself as a shoe company. Today, it has divested itself from a tangent shoe segment in order to pursue athletics directly. Its mission is to bring “inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world.” Identifying its user’s terrain (athletics) and marking its territory (inspiration, innovation, global) enabled Nike to move into consumer electronics (Nike+), or even health generally. Customers choose Nike because it’s not just about shoes, it’s about athletics.

Businesses thriving today on new market dynamics, from technology to brand leadership (Apple being a potent mix of both), are paving a new strategic path others can follow.

Not all firms are employing the same model, but each are discovering new ways of working. Next generation companies are questioning historical precedents about scale, productivity, centralization, sourcing, and talent. Innovation is emerging as a discipline rather than an exception. New ideas about problem solving, agile prototyping, and socialized innovation are leading to new breakthroughs.

The success of the industrial era is yielding a post-abundance era of choice. Companies built for scale will need new strategies – new ways of seeing and criteria for making decisions.

Design thinking is emerging as a significant approach for finding and building upon new opportunities.

New Lenses

Disruptive change of this sort forces leaders to get back to basics. Category and company orthodoxies should not be taken as givens as firms try to answer two fundamental strategic questions: Where are you going to play? and How are you going to win? These two questions sound deceptively simple, but getting to answers requires new a way of seeing.

Deciding where to play involves better understanding the context of your business through the eyes of the customer. Most businesses view themselves as a provider of a product or service, but they might be better served to describe what they do in terms of customer value. What companies sell isn’t always what customers buy.

User research can be used to discover what Patrick Whitney calls user "terrains" – a collection of motives, priorities and aspirations that comprise a way users think about their goals. Starbucks makes money by selling coffee, but it sells a larger envelope of activities – a place to meet a friend or colleague, to learn about music, browse merchandise, or learn about coffee. Nike sells shoes but focuses on athletics. Disney sells entertainment but focuses on fantasy experiences (“magic”). Identifying user terrains can expand a company’s opportunity area for innovation. Understanding what users value is a step toward creating meaningful value propositions.

After learning about the user goals, a company needs to decide how to identify their "territory" – a focus on how they’re going to win. What else might the company offer to help the customer accomplish her goal? User terrains are what customers do or want, and the company’s territory is how they’re going to help customers succeed. It’s like positioning, except categories are defined by customers rather than similar companies, and the claim is a specific subset of the category rather than a broadly inclusive offering.

Answering the key strategic questions enables system-level planning: What are the key customer touchpoints in your company territory? What is the exchange of value between people and organizations that motivates participation?

Customer touchpoints are parts of your new aligned system – key customer interactions, often enhanced by things you can make. Frameworks like “poems” (people, objects, environments, messages, services) can be helpful to identify and describe system components.

Understanding how people make decisions, what and how people assign value, is at the core of behavioral science. What is clear from this area of study is that much of the value exchanged goes beyond money. Mapping these value relationships in a networked fashion can be described as a value web – in contrast to the more linear value chain.

Once a new system is established, consider how to express your value through a customer experience. What will your new or evolved offer be like? What needs to be done? When?

A human factors lens is useful for considering what a new experience will be like. Considering 5 key human factors – physical, cognitive, social, cultural, and emotional – is helpful for greater coverage.

Mapping a customer life cycle or journey is a way to consider time in your offer. Touchpoints can be mapped as a linear customer experience by business objectives (i.e., awareness, convince, buy, support) or user objectives (consider the “5E’s” – entice, engage, enter, experience, extend).

Activity systems maps activities and dependencies to help plan how it is going to happen, and who is going to do it. In a networked knowledge economy, only some of these systems are in the company.

Finally, road maps, starting with envisioning and backcasting to the present, can help describe when you expect things to occur.

People: The Hidden Lens

People are the real drivers of change, though company culture is too often overlooked. Cultural orthodoxies (unwritten rules everyone follows) can extinguish even the best strategy.

People will support what they help build. Collaboration is critical in an era redefining boundaries, but true collaboration is hard. Collaboration – as opposed to merely cooperation – requires that team members admit shortcomings in order to dovetail with others’ strengths. Often teams can get along, but don’t always jointly work toward a common goal.

Innovating in an era of choice often requires a willingness to be lost in the problem – a solution that has no clear path to success. Team members with different backgrounds need collaboration and communication skills in order to effectively solve new kinds of problems.

Organizations with an eye toward the future will create people systems designed with change, motivation, collaboration, and communication in mind.

New Skills

Recognizing change, seeking new paradigms, and using new lenses require new skills. The emergence of "design thinking" is one of the innovation discipline trajectories in the new era of choice. Design thinking is dissecting and describing an ideal design process for the purpose of increasing engagement (teams) and making it repeatable (a process).

Great designers exhibit these skills intuitively, but that may not be enough. There is a great need to innovate more reliably. As we seek to understand how Google and Disney innovate in the face of change, we build a vocabulary for the nature of innovation.

Solve the right problem

People often see themselves as problem solvers, but consider: What is problem solving? Problem solving is an emerging discipline. Start by thinking about problems as inputs and outputs. What is going in, what is coming out? Creating something new often involves unbundling and recombining.

Problem framing, and reframing (defining the problem differently) is a powerful tool for making progress. Consider how abstractly or concretely the problem is defined, causes and effects. You may be a "big idea" person, but try to avoid being an ADD reframer. Reframing too late can derail the best project.

Think in systems

Look for, find, create, and leverage patterns. Simple systems are better. The right constraints are productive. Have empathy for project sponsors, understand business goals and historical strategy models, and look for parameters.

Making is thinking

Language is abstract, but physical prototypes encourage decision making. Meaning is co-created. Use prototypes as communication boundary objects – tools for collaboration and failing fast. Language itself is tricky, words and measurement create orthodoxies of thought. After all, communication is not one way – it is shared. Broadcasting is not communicating.

Understand people

People are complicated. They ask for something new but often reject it when they see it. What do you take as a given? What is your bias? Then consider what is genuinely different, and models for generating and communicating the something genuinely new.

Customers will tell you what want, but they often don't know what they need. How many customers asked for the iPhone? People ask for choice but crave simplicity. Consider how people make decisions, behavioral economic theory, and personal motives. Consider organizational orthodoxies and models for change.

Empathy is not a luxury. You are not likely to be your customer or user of your product or service. Seek a deeper understanding of the user context, behaviors, goals, and activities.

New lenses and skills will not solve all problems, but they are new tools to help us chart a course in our an emerging era of choice.

Much credit for this content goes to the smart people at the Institute of Design including Patrick Whitney, Jeremy Alexis, Marty Thaler, Kim Erwin, Hugh Musick, and many others. This is a lot of their thinking, here through my own lens.