Peopledesign

The Built Environment

Furniture

Lighting

Textiles/Upholstery

Flooring/Carpet

Building Materials

AE Firms

Productive Progress

Productive Progress

What do we mean by productivity?

Every business, manager, and team wants to be more productive. People want meetings to be productive. Sometimes people want their weekends to be productive. Not being productive sounds like wasting time. We want to be more productive, but productivity is an elusive goal.

What do we mean by productivity? A quantitative measure is the simplest – things we can count. We envision an assembly line of tasks. Being more productive means increasing the line's speed or checking off more tasks in a certain period. We’re rewarded if we increased productivity by 20% last quarter.

People old enough to remember Lucille Ball may recall her failing and rebelling against assembly line tyranny in the 1950s. We’re fighting a losing game, Lucy says. Speed it up, the boss says.

Capitalism offers a model for productivity – a balance of producers and consumers. Producers produce, by definition, and being a good producer often means producing more. Good consumers consume more. The wealthiest nations have become very good at producing and consuming to the point where we produce and consume too much. When we have “peak stuff,” people seek a healthier balance, sustainability, and mindfulness.

We want technology to help. Task managers run amok in the saas landscape as we attempt to organize a complicated world, but knowledge works look less and less like assembly lines. At some point, it’s not only about quantity. It’s about quality.

While Lucy was lampooning the assembly line on TV, the Toyota Production System was invented in Japan. In a time when most companies focused on volume, Toyota emerged as a global leader focused on product quality. Western companies adopted the philosophy in the 1980s, and it became a worldwide manufacturing productivity revolution. The first step of TPS is to address the waste of overproduction.

A chief aspect of TPS was to champion the “Andon Cord,” where anyone in production could stop the line to ensure quality. In a previous generation, stopping an assembly line would be like treason. Lucy needed an Andon Cord! Toyota emphasized the importance of an individual qualitative judgment call, sacrificing short-term quantitative productivity. In a late-stage industrial economy, making tons of cars wasn’t enough. We had to learn how to make better cars.

Qualitative judgments make people nervous. It’s not unlike the assembly line, where we can count items, speed, and time. Black-and-white distinctions are easier to delineate than grey ones, but we live in an increasingly nuanced world. Qualitative differences account for non-logical customer choices, surprising new competitors, and uncomfortable trends.

Our mental model for a 40-hour workweek is like an assembly line. As a culture, we’ve come to accept quantitative parameters for what it takes to be productive – eight hours a day for five of seven days. We measure many things, but we see time as an inherent measure of productivity. Considering billable hourly rates, we’re also using time to measure value. The model works, or it has worked well enough, so we accept it.

But the world of ideas – knowledge work – doesn’t know those boundaries. Have you had a good idea in the shower or just before you fall asleep at night? Good thinking also happens even when you’re not “on the clock.” People are pretty good at wasting time from 9-5. How do ideas fit on a Gantt chart (a hundred-year-old model for tracking systematic routines)? How long does it take to have a good idea?

It’s not only covid and generational change that’s challenging the 40-hour work week, forcing issues of hybrid work. These trends have been coming to the mainstream for decades, perhaps only now coming to fruition. The right cocktail of a pandemic, technology, and a post-industrial society is forcing organizational leaders to find new ways of thinking about work and productivity.

When untethered to an assembly line, productivity is more personal and flexible. Many accomplished writers, scientists, and politicians held unconventional schedules. Winston Churchill, Leonardo da Vinci, and Thomas Edison were famous for napping. Ernest Hemingway wrote every day but only until noon. Edison worked through the night, only sleeping for three or four hours. Were these people crazy or lazy? Are unconventional routines reserved for productive geniuses, or is productivity enhanced by finding flow?

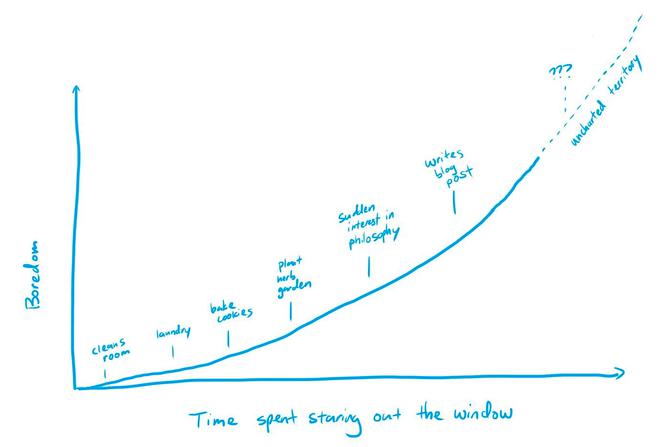

Albert Einstein walked one and a half miles to Princeton and back each day, which he viewed as cherished thinking time. We might consider the value of “non-productive” time, boredom, and activities that are hard to measure but clearly valuable.

Office providers have longed to make a connection between their products and productivity. The argument is that the right worksurface, ergonomic chair, storage access, adjustments, lighting, acoustics, materials, line of sight, privacy, etc., increases productivity. It probably does, but so does taking a walk. As desktops became laptops, “office” became more of a verb or state of being rather than a place.

In-person work. Most office products support same-time, same-place in-person work. Office providers might consider the new world of work, which enables other possibilities.

Distance work. Same-time, different-place “distance” work has become a new standard (web calls, anyone?).

Independent work. Different-time, same-place, “independent” work coffee bars and other third places thrive.

Asynchronous work. Different-time, different-place “asynchronous” work fuels the saas economy.

Distance, independent, and asynchronous productivity modes are on the rise. How is this kind of work enabled, facilitated, and enhanced?

Productivity today is less bound by time and place. We all know it, even if we don’t know how to manage it. Empowered workers may have conflicting incentives with employers with sunk infrastructure costs, but we all benefit from an evolved sense of work, balance, and productivity.

In a larger sense, productivity means progress. In what direction we aim to progress will shape our understanding of forward motion. Productivity may be as challenging to define as humans are complex, but we can evaluate quantitative and qualitative measures. We aim to create the best work products most efficiently. We oblige ourselves to produce, consume, and watch the clock.

We also need time to reflect and connect.