Peopledesign

The Built Environment

Furniture

Lighting

Textiles/Upholstery

Flooring/Carpet

Building Materials

AE Firms

Beyond Optimization

The New Market Landscape

Evolving Beyond Optimization

We live in one of the most significant periods of change in human history. Companies must evolve proactively to keep up with the people they serve.

It’s not news that we are living in a new era. Call it the Knowledge Era, the Information Age, the Digital Age—call it what you will—the evidence of change is all around us. From technological innovations to globalization, social change, and political unrest, some believe we are in one of human history's most significant periods of change. It may be hard to measure accurately, but there is little doubt that we are living in new conditions.

We can’t operate the same way and expect the same results. New circumstances warrant a different response. We need a new template, a different way to think about work and teams.

Let’s consider where we’ve come from and envision where we're going.

Every two days, we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization until 2003.

Eric Schmidt, Google

Yesterday

We are emerging from the Industrial Era. The Industrial Revolution occurred in several phases over the last few hundred years, shaping modern life today. Industrial processes have been incredibly successful in bringing essential and desirable products and services to billions of people. As a global society, human ingenuity has improved lives in unprecedented ways. The results are imperfect, but the success of the previous era is hardly in question. The achievement of the Industrial Era has enabled us to see the next horizon, but we face new headwinds.

The wake of the Industrial Revolution is an industrial mindset. In mature economies, much of civilization is the result of industrial processes descending from the assembly line. Assembly lines, a “series of workers and machines in a factory by which a succession of identical items is progressively assembled,” are a signature achievement of the industrial era.

Before large-scale industry, goods were made by hand in small workshops. The shoemaker, the blacksmith, the tailor. At this point, the significant challenge for most people was about access. Having a product – let's say, a shirt – depended on having access to someone who made shirts. It wasn't a question about how many, instead, whether you had enough.

The craft era was about scarcity: You were lucky to have a shirt.

Assembly lines changed all that. Industrialization allowed us to leverage technology to create more things quickly and efficiently, reaching more people. The industrial revolution enabled manufacturing and distribution at scale. For people in mature economies, essential access is less of a concern.

Industrialization means everyone gets a shirt.

Assembly line workers at the Ford Motor Company factory at Dearborn, Michigan. Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Global industries and market players have scaled to meet our growing demands. Many organizations have themselves grown to an industrial scale. In the late 20th Century, organizations shifted their focus from scaling up to optimization – making the same things even more efficiently. The Quality movement, Toyota Production System, and Six Sigma processes focused increasingly on optimization on continuous improvement. These ideas helped modernize assembly lines, achieving unprecedented efficiency, quality, and speed.

We have a closet full of shirts.

The expectation of organizational scaling and efficiency persists. We will continue to optimize industrial manufacturing processes by leveraging automation, robotics, artificial intelligence, and new technologies on the horizon. At this point, however, some have described that we may be reaching "peak stuff." Ways of organizing our lives – and all our stuff – are on the rise. Buying more closet organizers, books and magazines the encourage reduction and simplifying, and retailers that focus on curation are all indications that our cup runneth over.

We have too many shirts.

Supporting a greater scale and efficiency is a price of entry for many industries, but eventually, it may be like seeking blood from a stone. It’s a signal that we may be at the end of the industrial era. Perhaps we are collectively overcoming our innate survival motive based on scarcity – hunting and gathering, farming, collecting, and squirreling it away for the future. Our collective values may be pivoting. Always wanting more isn’t helping our physical health, emotional well being, or the planet.

Today

The success of the industrial revolution governs how we think today. This is understandable, but we sometimes are shaped in ways that are not readily apparent. Most of our organizations, institutions, and infrastructure – business, education, healthcare, government – are products of an industrial mindset. Assembly lines were a significant innovation for achieving scale and optimization. However, they are also linear systems with predetermined paths, which carries inherent risks with the challenges ahead.

Our organizations have been shaped by assembly lines, but too much assembly line thinking is a risk. Too often, we think about employees, students, and patients as pieces on an assembly line. We aim for repeatability, uniformity, and efficiency. We seek employee KPIs, standardized tests, student yield rates, and hospital bed turnover rates. We think about government as either grease or friction in a machine. Of course, metrics are not inherently problematic – after all, assembly line thinking helped us scale to meet the demand of a growing society. However, this dynamic is changing. Peak Stuff will lead to new customer objectives.

In Zero to One, author Peter Thiel describes the need to create something from nothing: To create something genuinely new. Theil recognizes that traveling more efficiently will not help us get somewhere new. Theil is a proponent of starting over with a clean slate and erasing what isn't working. All leaders should strive for this kind of clarity. As Netscape founder and Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen famously observed, software may be "eating the world”, but hardware and people move more slowly.

Our modern world was made brick-by-brick by assembly line thinking. As our world gets more complex, linear thinking is not enough. At this point, we live in a world of systems: Railways, highways, roads, bridges, airports, houses, cars, subways, water systems, sewage systems, electrical systems, and so on. We need to think differently about how we manage complexity, how we make choices, and how we think in systems.

In 2010, Eric Schmidt, of Alphabet (Google), stated that "Every two days now we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization until 2003." There are many statistics like this, such as how many New York Times volumes of information is produced at what pace, etc. Regardless of the details, the effects are dramatic. The sheer volume of available information has changed from droplets to an ocean, and it's not clear if we as a society are yet ready to handle it. Never before has so much data been produced, accessible by so many. Never before have so many people in the world been so connected.

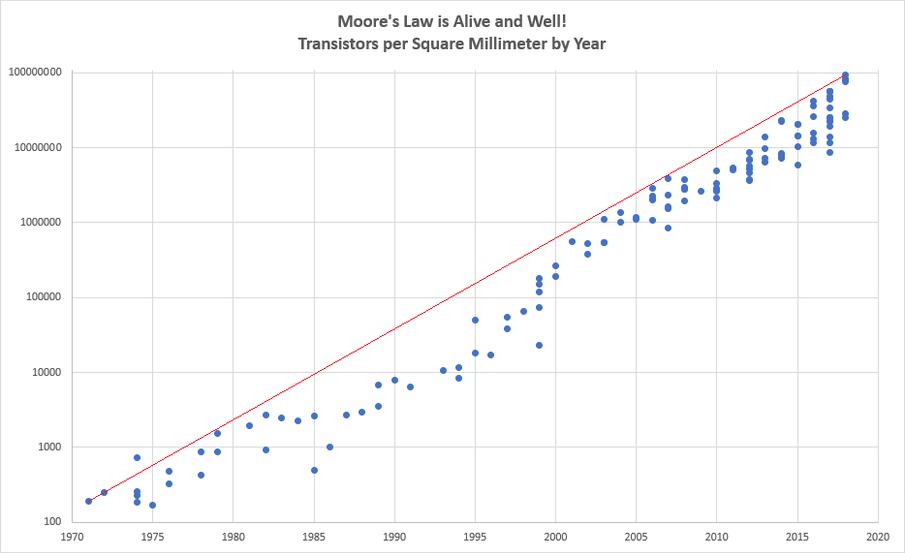

Chart by Eric Martin

In 1964, Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel predicted that computing power would double every 18 months at half the price. This came to be known as Moore's Law and has been true ever since. The acceleration of computing power is exponential, rather than linear like assembly lines. It’s isn’t just moving faster, it’s different in orders of magnitude.

We don't know the impact. In fact, we might need another 20 years to catch up with the implications of Moore's Law – even if it stopped today. Consider how mobile technology is changing business or how social media is shaping democracy. Consider the impact of the emergent sharing economy on the hotel business (Airbnb), or ride sharing is having on the taxi business (Lyft, Uber). Each of these disruptive innovations was built with new but existing infrastructure (smart phones, location services). The potential of an internet-enabled mobile device has the ability to change entire industries, and they’ve only been available for a decade. We don’t yet know the impact of smart products, self-driving cars, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence.

It is tempting to see these changes and assume that we are at the height of the knowledge era, but there is a lot of evidence to suggest that we are only in the beginning. If you believe that we are in a time of great change, consider where we were in 1920s, and what happened by 1970s. If we consider the potential impact Moore’s Law and the accelerated We may see even more change in the next 50 years.

New infrastructure is being laid by tech giants, enabling even greater change. What lies ahead isn’t certain, but we know it’s not likely to look like the past. The post-industrial economy will have a different character. A new organization will need to be agile enough to adapt to these changes, and be ready for what’s next.

Tomorrow

Peak stuff has led to a new problem: Choice.

As Henry Ford famously quipped about the Model T, an early assembly line success: Customers can have any color as long as it's black. Industrial processes were built for uniformity, not choices. Optimized manufacturing organizations know how to make products efficiently but may not know what to make. That's an entirely different kind of problem, which is less about repeatable industrial scale and more about customer choice.

Customers today have more choices than ever. As we have evolved from a craft era, where you were lucky to have a shirt, through an industrial era, when everyone gets a shirt, we face a new problem: A closet full of shirts. Having too many shirts doesn’t lead to more shirts, but deciding which one to buy or wear, shirt editing, and curation. Overabundance may lead to more fundamental questions about product ownership, storage, use, life cycle, and disposal.

Beyond the age of information is the age of choices.

Charles Eames

Technology innovation and globalization has flattened business categories. Just ask the local retailer about Walmart, the local record store about Apple Music, or the local bookstore about Amazon. Some of these categories may have been low-hanging fruit, ripe for change with more advanced distribution approaches.

With more fundamental changes on the way, seemingly impervious industries will be vulnerable. It’s not just local retailers. Now it’s hotels, car services, and offices that are subject to new business models. Increasing segments of the economy will feel the impact of globalization and digital transformation.

The industrial era's gifts were processes for achieving scale and optimization. These competencies remain vital, but these older problems are understood. The new problem, customer choice, will necessitate new organizational changes.

Business school itself is a kind of industrial idea. Business management as a discipline stemmed from assembly line thinking and led to a kind of industrial, centralized command-and-control. In an era of TED Talks, Khan Academy, and the explosion of online learning, even the idea of a few years of graduate school being sufficient to become a leader throughout your career seems dated. Still, many organizations are structured in ways that resemble industrial factories. While much has changed in 100 years, let alone the last decade, many organizations rely on principles from a previous era.

In his article, The Coming of the New Organization, business guru Peter Drucker explored the a shift from manual or clerical work to knowledge work. Knowledge is inherently specialized. He described knowledge workers as more like musicians in an orchestra than cogs of a wheel. Musicians are specialized but organized in groups. They collaborate, communicate, harmonize, and improvise. A conductor facilitates and sets the tempo. Together, they create something human, organic, artistic.

Industrial processes tend to be top down, but specialized knowledge work is more bottom-up. This has an impact on how information flows and organizational hierarchy. It has an effect on training, language, and metrics. Knowledge work depends on information sharing. In a word: communication. The “faint, unfocused signals that used to pass as communication in a traditional organization won't translate to the new era.” As we move from a focus on scale to choice, we will think less about optimization and more about connections and communication.

Technology is changing what people do and how they do it. Job functions will change. Organizations of all kinds, and society at large is starting to just come to terms with what these changes will mean.

The New Organization will be more agile than its industrial predecessors. In the Darwinian sense, it will adapt and adjust to the changing environment in order to survive. The new conditions include a move from not only scale and optimization, but also to be a brand of choice. Customers will vote with their purchases, reflecting their understanding and habits.

Peter Drucker said that the purpose of business is to create a customer. In an Era of Choice, customer relevance is the new currency. The New Organization will create customers by being a brand of choice.

Get Started

Small steps in the biggest direction.