Peopledesign

The Built Environment

Furniture

Lighting

Textiles/Upholstery

Flooring/Carpet

Building Materials

AE Firms

The Reach of Design

The Reach of Design

In Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek claimed that “design can reduce pollution, overcrowding, starvation, obsolescence and other modern ills.” From aesthetics to usability, ethics to equity, it's essential to consider what kinds of problems design can solve – and perhaps more significantly, what problems it can't solve. What can designers do? In this brief talk, we explore the boundaries and opportunities of design.

This talk is from WCD, the World Class Designer Conference, a 24-hour global event in 2021 to make a direct and tangible investment to the design community in Africa. Kevin was among the keynote speakers. The transcript is below.

What is the reach of design?

In a recent IxDA event, the book entitled The Limits of Growth was frequently referenced. It's appropriate in this era, as we evaluate climate change, ethics in technology, and other critical issues.

An excerpt from the book reads: “If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years.” It’s a sobering thought which deserves our gravest attention.

I want to call your attention to this part: “we will reach the limit of growth within the next hundred years” was written in 1971 – 50 years ago! So, we should be halfway there. How are we doing? Not great, I’m afraid. This reality check should trigger action, but these ideas are not new.

Interestingly, Design for the Real World by Victor Papanek came out the same year. Papanek claimed that “design can reduce pollution, overcrowding, starvation, obsolescence and other modern ills.”

All this led me to wonder about the reach of design. These ideas are as old as I am, but have they taken hold? Why was everyone talking about it at Interaction Week? Are we close enough to the brink where we must take action? What can design and designers do?

Spoiler alert: I don’t have answers. As any good designer strives to do, I try to ask good questions. I do have some opinions about these things, which I will share, but we should ask: What kinds of problems can design solve?

After telling people I’m a designer, many people from outside the design world ask, “what do I design?” Well, “many things,” I say, which sounds pretty sketchy to a doctor or a chef. The answer may not be as easy as you might think. Here is perhaps a more important question: What kinds of problems can design not solve?

Many people have adopted design thinking approaches to drive innovation and organizational change. They have no problem taking on just about any challenge, so let’s think about this.

Some of the most critical challenges of our era today include increasing sustainability, combating racism, dealing with the effects of colonization, misogyny, and equity in general. These are big problems. Huge! For many people in powerful places, designers are the last people they’d ask to help find a solution.

Designing systems is increasingly the domain of designers, so these can be design problems. However, an aspirational and high-minded designer might say: Well, these are all systems. It could be, but that’s a tall order.

In preparation for today’s discussion, I reached out to my friend Rob Girling of Artefact, a Seattle-based firm focused on “Responsible Design.”

Rob told me that they’re trying to define what that means, and in his case, it means considering fairness (weighing the ethical impact of all stakeholders), thinking long term (the systemic forces affecting the future), being considerate (thinking about the potential effects of the work), and purpose (customers over profit).

These things sounded great to me on paper, but made me wonder what it looks like in action. Many designers may have this kind of spirit but feel like they lack the power to affect change.

A few years ago, Alan Cooper gave a talk at Interaction Week in Lyon, France, considering design ethics. Cooper suggested that while designers may not always have the direct power to influence change, they may have the agency to control how products and services are created because they literally have their hands on the switch. Perhaps some designers don’t have power, but they have agency.

Kevin served on the IxDA (Interaction Design Association) global board for five years, the last year as its president.

The idea of agency sounds good to me, too, but it reminds me of the tale of the Dutch boy who has to put his finger in a cracked dike to prevent the water from the reservoir from destroying the town. It’s an urgent need. The boy has agency and is a hero, but it’s not a sustainable way to save the town.

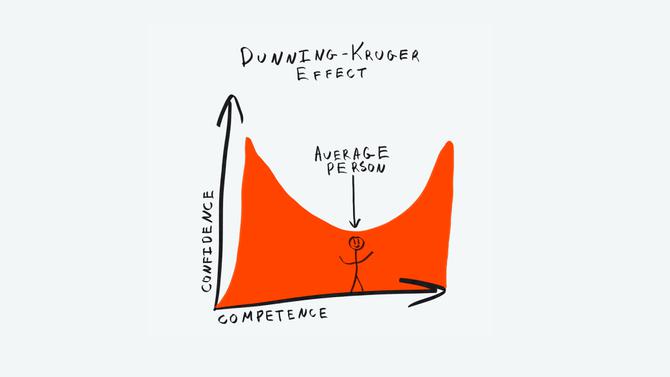

What is designer agency? Doctors and chefs may not understand how naïveté can be a superpower. Charles Eames said, “Sell your expertise, and you have a limited repertoire. Sell your ignorance, and you have an unlimited repertoire.” I’ve had plenty of first-hand experiences where I, the designer, can see things that all the experts can’t. Groupthink occurs in many teams, companies, and industries. It’s hard to read the label outside a jar you are inside. It’s what, as designers, we feel comfortable skipping around climate science, ethics, technology, psychology, philosophy, research, production methods, culture change, team dynamics, etc. If you like to be a sponge, it’s great to be a designer!

As designers, we should be eager to learn but respect other competencies. On the other hand, we are at risk of perpetually being at the first peak of a Dunning-Kruger Effect curve, where our confidence peaks when we first learn a few new ideas. A little knowledge can be dangerous, so we call the first spike the “Peak of Stupidity,” whereas actual competence takes much longer to acquire.

Many believe that the future of craft will be as much about machine learning as hand-eye coordination. Advocates of design thinking applaud designers’ ability to skip between disciplines to tease out innovation or move toward consensus.

Does a wall of post-its make you smile or groan? Despite what you may think, I believe design thinking is real, even though it’s not always well defined and gets abused. Post-it parties can waste much time when everyone gets a say, and nothing gets done. Collaboration is tremendously valuable, and design skills can play a pivotal role.

Design thinking has taken root by applying these methods to “wicked” problems – vs. merely hard ones.

Hard problems require expertise but have a formula that can be researched, studied, and mastered. It’s hard, but the path is known. We might think about mechanical engineering or performing surgery as hard problems. On the other hand, “wicked” problems are problems that are hard to define, let alone address. What do we do about poverty or unhealthy lifestyles? There is no obvious solution.

One answer is that design solves people problems. We named our firm Peopledesign because of this notion – the idea that design is primarily in the service of people.

People are complicated. If it was possible to understand the nature of consciousness, bias, and behavior, perhaps these wicked problems could become hard engineering problems, but for now, they are design problems.

Design, as we think about it today, emerged from the industrial age. Before industrialization, makers and users of products and services were very close. They were in the same family or town, or even the same person. You could get a pair of shoes if you knew someone who made them.

Industrialization allowed production at scale, moving makers away from users. The gap led to ideas about standards for safety, usability, and aesthetics.

Today, makers and users usually don’t even know each other and are merely an abstraction of markets or brands. Design emerged to fill the gap, helping to better connect people with the things and experiences created by makers – other people. The designer’s role has been – and continues to be – about creating better connections, increasing understanding, and improving experiences.

From my point of view, the two primary skills of a designer are framing and prototyping. We have some agency and opportunity to prototype responsible systems. Explaining these things is a whole different talk, but suffice to say that more significant cultural issues are on the menu because we can help reframe how to think about these wicked problems.

A new era requires new skills. Designers may be naive about many subjects, but so are all experts. Design is a kind of meta-skill that can serve many different purposes and teams, sitting alongside other meta-skills, including management and strategy. No wonder business schools and management consulting firms have adopted design.

Are there problems design can solve and others that it can’t? It’s not an easy question to answer, but what is clear to me is that design is a way of thinking and inspiring action which can play a role in an increasingly complex world that needs answers.